Cindy Claure-Veizaga has created this guide to online resources about Barry Farm in Anacostia, Ward 8. Washington DC. This serves as a supplement to the student-authored website, Southeast Voices: History and Memory in Barry Farms, Ward 8 (Holding on to Home: The Untold Story of Barry Farm)

See all student-authored online community research exhibits for Dr. Auslander’s Raceaand Racism (Anth 210) Fall 2025, American University at: https://markauslander.com/2025/11/25/community-research-projects-race-and-racism-anth-210-fall-2025-american-university/

Overview The video introduces Barry Farm as a site with a long history of community building and subsequent displacement in Washington D.C From indigenous communities to formerly enslaved people building a thriving Black community, and later a public housing complex, the area hasundergone continuous shifts. The rapid pace of gentrification continues this cycle, displacing residents and tearing down homes (1:12-1:41).

—Barry Farm: A “Gold Mine” for Developers.

Residents express their sadness and disbelief at the demolition of their homes. One community member states, “Now you’re just here the demolition and homes being torn down… this is like a lot of land, this is like a gold mine to the developers” (2:00-2:10). This highlights the economic forces driving the displacement, where land is seen as a commodity rather than a home.

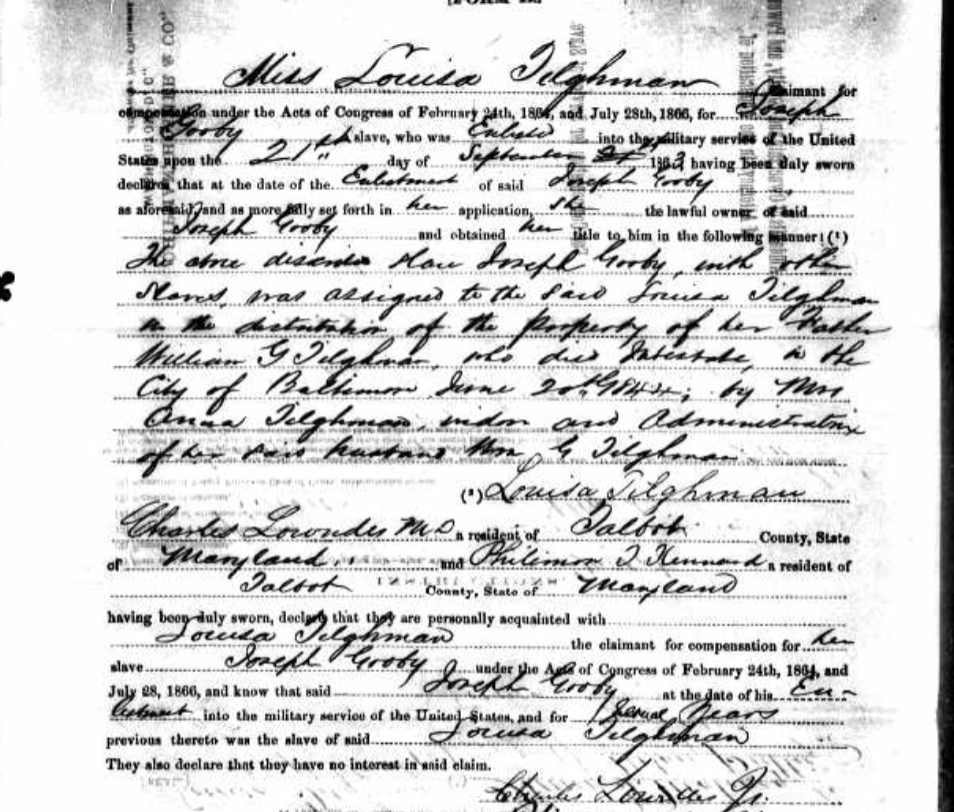

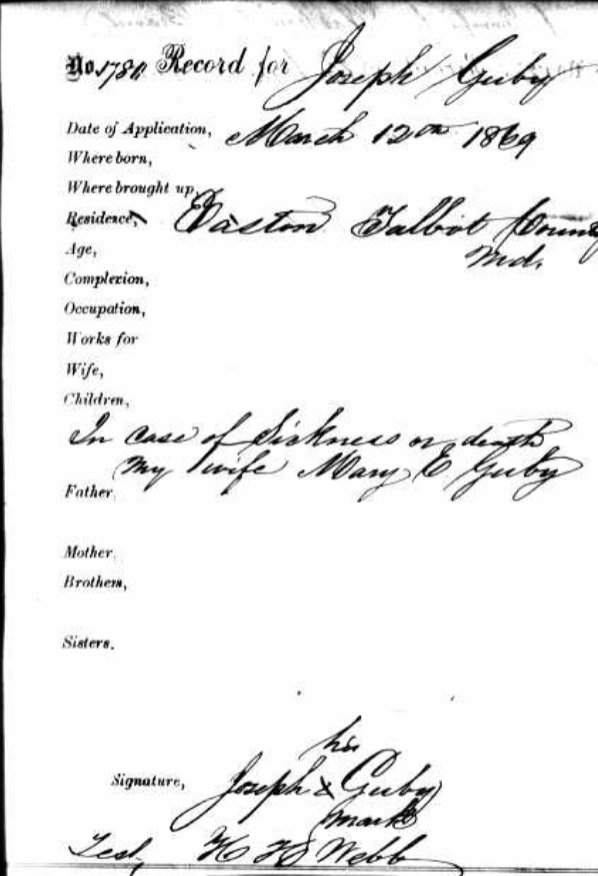

The Origins of Barry Farm: From Plantation to Freedmen’s Village

The film delves into the origins of Barry Farm, revealing it was once a plantation owned by a slave-owning planter named Barry (3:28-4:53). After the Civil War, the Freedmen’s Bureau

purchased this land and sold plots to formerly enslaved people. This allowed them to build a life for themselves, though residents note, “this wasn’t even that, this was people who purchased the land right, they weren’t given the land… I still feel like it was really their birthright to be able to be landowners because that was one of the many things that had been denied them for so longeven though they work the land themselves” (7:15-7:39).

A Thriving Black Enclave and Homeownership

Early residents of Barry Farm, including reverends, teachers, builders, and farmers, created a“thriving black enclave” (12:11). They built their homes and cultivated their land, creating asuccessful neighborhood. The video emphasizes its legacy as “a black ownership community inD.C” (12:54-13:00). A descendant of Emily Edmondson, one of the founding members who escaped slavery, reflects on the freedom he now has to walk the same streets his ancestors had tosneak through for freedom, saying “it just resonates with me that not long after they had to sneakthrough those streets for freedom I had the freedom and I could just walk those streets”

(13:51-14:01).

The Public Housing Era: A Haven and A Home

In the 1930s and 40s, a public housing complex was built on Barry Farms due to segregation,offering housing to African Americans who migrated to D.C. Residents describe it as a “perfectcommunity, a haven” (16:43) where “everybody took pride and kept their homes up” (16:47-16:59), highlighting the strong sense of community and support.

Civil Rights Activism and the Fight for Dignity

Barry Farms was the core of Civil Rights activism. Students from the dwellings successfully

challenged segregation in D.C. public schools (24:09-24:30). The “Band of Angels,” led by Miss Etta Horn, fought for the rights of welfare recipients, ending intrusive home investigations and advocating for dignity. A resident recalls the feeling of activism “it made you feel wonderful, it made you feel good you were doing something” (27:54-28:00).

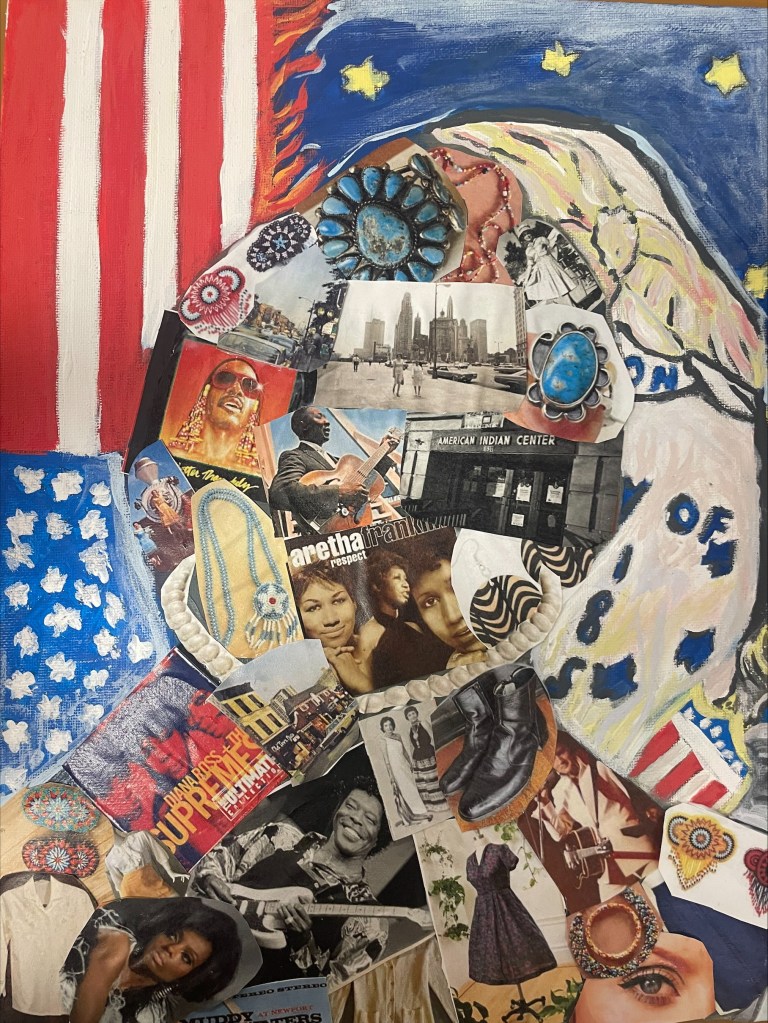

The Rise of Go-Go Music and the Junkyard Band

Barry Farm became an “epicenter for Go-Go” (31:40-31:43), with the Junkyard Band emerging from the neighborhood. Members of the band, who started with homemade instruments, credit their roots, “wouldn’t be no junkyard without Barry Farms because we are very fun”

(32:00-32:05).

Go-Go music provided a unifying force, bringing people together. (31:12-31:15)

Neglect, Stereotypes, and Displacement

Decades of neglect led to the deterioration of the dwellings, and Barry Farms became unfairly“synonymous with drugs and crime” (35:58-36:01). Despite the negative stereotypes, residentsmaintained a strong sense of community, stating, “it’s still overall a good place, a lot of peopleneed these houses, it was a lot of families here that were my family over there, family, family”

(36:34-36:45).

This section concludes with the heartbreaking reality of mass displacement, a

“nightmare” (40:39-40:41) with residents unsure if they will ever return.

A Fight for Preservation and Sacred Space

In 2019, residents organized to preserve some of the remaining homes as historic landmarks, advocating for their history to be remembered and their stories told. One resident passionatelystates, “what remains of Barry Farms is too important in the development of this city to go thebulldozer” (46:07-46:13). While only five dwellings were preserved, it was a significant step.

The section ends with a powerful reflection on Barry Farm as a “Sacred Space” (47:39-48:16), aplace where “blood, sweat, and tears” (48:24-48:34) were shed, and where joy and triumph were also found.

2. We Shall Not Be Moved: Stories of Struggle from Barry Farm–Hillsdale

Stories of Struggle from Barry Farm–Hillsdale (on line exhibiiton: Anacostia Community Museum, Smithsonian)

Barry Farm–Hillsdale was founded in 1867 as a place where formerly enslaved African

Americans could own land and build independent lives. For generations, residents created

homes, churches, schools, and political networks rooted in self-determination. Even after

demolition in 2019, the community’s legacy of resistance and organizing endures.

Building Freedom After Emancipation

Land ownership was central to freedom at Barry Farm–Hillsdale. Residents built homes and

institutions with limited resources, shaping a strong sense of independence and political

awareness. Longtime resident Pierre McKinley Taylor recalled early life without basic

infrastructure, “When we first moved on Nichols Avenue we didn’t have running watter… Youeither had a well or you had a system.”

Place, Memory, and Community Roots

An 1867 map shows Barry Farms–Hillsdale as a connected community of families, churches, and schools. Leaders such as Frederick Douglass Jr. and Solomon G. Brown lived alongside working families. Churches like Mt. Zion AME and schools such as Howard School anchored civic life, reinforcing how land and place shaped belonging.

Voting Rights and Women’s Political Action

Residents viewed voting as essential to full citizenship. In 1877, men and women from Barry Farms–Hillsdale signed a petition to Congress demanding women’s suffrage. Their action linkedlocal struggle to national movements and showed a belief in shared political responsibility acrossgender lines.

Fighting for Basic Services

For decades, the neighborhood lacked running water, paved streets, and sanitation. Residentsorganized repeatedly for essential services while adapting to neglect. Reliance on wells andrainwater was both a necessity and a reminder of unequal treatment by the city.

Resisting Redevelopment and Displacement

Beginning in the 1940s, officials labeled Barry Farm–Hillsdale a “slum” to justify demolition. Residents rejected this narrative and fought back. Activist Ella B. Pearis remembered confronting Congress directly, “They said this was a slum… We went to congress… We defeated them.”

Challenging Segregation

Residents protested discrimination in employment and public spaces. During the 1940s, pickets targeted White-owned businesses that refused to hire Black workers. Activist Norman E. Dalelater believed his military draft was retaliation, revealing the personal risks of resistance.

Integrating the Anacostia Pool

African Americans were barred from the Anacoatia Pool, forcing children to swim in the

dangerous river. In 1949, youth from Barry Farm–Hillsdale challenged segregation through

repeated attempts to enter the pool. After arrests and clashes, the pool reopened in 1950 as an

integrated facility without incident.

School Desegregation and Its Limits

Families from Barry farm–Hillsdale challenged segregation through Bolling v. Sharpe. While theSupreme Court ruled segregation unconstitutional, residents knew legal change was not the same as social equality. Gerald B. Boyd explained: “There is a difference between desegregation and integration… integration… is mental.”

Black Power and Community Control

In 1966, Stokley Carmichael spoke at Barry Farms Dwellings, popularizing the phrase “BlackPower.” The message resonated with residents who already practiced autonomy throughorganizing and mutual aid. They rally connected the neighborhood to a national movement for political independence and cultural pride.

Women, Welfare, and Housing Justice

Women led some of the most powerful organizing efforts. The Band of Angels fought for safe housing, welfare rights, and health care access. Lillian Wright summarized their philosophy,

“Since we live here, we are best qualified to advise… how the funds should be spent.”

Youth Leadership and Community Care Residents invested in young people as a form of resistance. Founded in 1966, the Rebels with a cause provided jobs, recreation, and mentorship to more than 1,500 youth. Their work offered alternatives to criminalization and strengthened community pride.

Environmental Justice and Health

In the 1990s, residents confronted toxic pollution from the Navy Yard contaminating the

Anacostia River. Activists like Dorothea Ferrell demanded accountability, linking Barry

Farm–Hillsdale to broader environmental justice struggles affecting Black communities.

Demolition, Loss, and Preservation

In 2019, Barry Farm Dwellings were demolished, displacing residents and erasing historic

structures. Yet organizing continued. Advocate Daniel del Pielago reflected, “An organized

group of people can win something, even if it wasn’t what we ultimately wanted.”

Why These Stories Matter

Barry Farm–Hillsdale’s history shows how Black communities resist erasure through collective action. Centering residents’ voices reminds us that struggles over housing, land, and power are ongoing and that this community’s legacy continues to shape fights for justice today.

Barry Farm–Hillsdale: Uplifting a Living History, Ensuring a Just

Future

Barry Farm–Hillsdale is a sacred site in Washington, DC, rooted in Black land ownership andcollective struggle since 1867. What remains today, five historic buildings and streets named forabolitionists, stands as evidence of generations who built community, resisted displacement, and

demanded justice.Preserving this site ensures that Black history is not erased amid rapid

gentrification.

Land, Memory, and Belonging

The land that became Barry Farm–Hillsdale has long been a place of belonging, from the

ancestors of today’s Piscataway people to formerly enslaved African Americans seeking freedom after the Civil War. Residents built schools, churches, and businesses, forming a self-sustaining community known as Hillsdale. Land ownership was not only economic security, but a foundation for dignity and identity.

Displacement and Survival

Government actions repeatedly disrupted the community. The construction of Suitland Parkwayin the 1940s displaced hundreds of residents, and public housing development replaced land taken from Black homeowners. Despite this, residents continued to organize, desegregate schools, and fight for fair treatment, proving that community life endured even under structural violence.

Organizing for Justice

Barry Farm–Hillsdale was home to national leaders in civil rights, welfare rights, and housing justice. Tenant leader Etta Mae Horn helped found the National Welfare rights Organization and advised Dr. Martin Luther King Jr. during the Poor People’s Campaign. The community’s legacy shows how local organizing shaped national movements for economic justice.

Culture as Resistance

Culture has always been central to Barry Farm’s resilience. From the Goodman League

basketball program to the formation of the Junkyard Band, residents created spaces for joy,

creativity, and connection. These cultural institutions remain active today, carrying the

neighborhood’s history forward and linking past generations to present-day DC

Barry Farm as a Sacred Space

Community members describe Barry Farm not just as housing, but as home. Junkyard Band

member Vernell “Wink” Powell captured this feeling, saying: “Barry Farm, to me, was like one big old grandma house.” His words reflect the care, familiarity, and shared responsibility that defined daily life in the community

Preservation Is About People

Preservation at Barry Farm–Hillsdale is not only about saving buildings, it is about honoringlives, dreams, and struggles. As ANC Commissioner Ra Amin stated during a preservation hearing, “Historic preservation is more than just buildings. It’s about people, it’s about dreams.” This perspective centers residents as the heart of preservation efforts

3. Website: Designing a Just Future

https://www.dclegacyproject.org/

The DC Legacy Project envisions the Barry Farm site as a living museum and active community space. Through design workshops and public engagement, former residents and allies imaginedspaces for learning, healing, organizing, and entrepreneurship. These plans emphasizecommunity control, cultural production, and economic opportunity rather than erasure

Why This Resource Matters

The Design Resource Booklet shows how history, design, and community organizing come

together to resist displacement. By centering resident voices and collective memory, the projectinsists that Barry Farm–Hillsdale remains a place of pride, resistance, and possibility past, present, and future

4. Barry Farm: Past and Present Part 1 (Youtube Video)

The Historic Significance of Barry Farms

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=vp8mOTJKq9M

Barry Farms holds a profoundly significant place in American History as the first free Black

community established in Washington, D.C after the Civil War (1:18-1:26). It was the initial

place in the district where black individuals could own property, a pioneering “model

community” (1:26-1:53).

The Origins: From Plantation to Community

The community’s name directly reflects its origin: it was once part of a large tobacco farm

owned by James Barry in the mid-19th century (3:06-3:27). This substantial 375-acre tract was later purchased by General Howard and the Freedmen’s Bureau. The intention was to sell one-acre lots to newly freed slaves, allowing them to work in the city or cultivate their land (3:37-3:57).

Early Life and Self-Reliance in Barry Farms

Barry Farm exemplified the industry and aspirations of African Americans (4:01-4:07).

Residents lived in clapboard cottages and raised animals, demonstrating remarkable self-reliance (4:10-4:21). Despite the primitive circumstances, it served as a powerful “reputation of the stereotype that blacks were ignorant and lazy” (5:05-5:14). It became a “shining example of what could happen if you only gave African-Americans a chance” (5:21-5:25).

The early residents were true heroes, clearing land, building homes with minimal tools, and walking long distances to work (6:06-7:10). Many paid for their lots through a purchase-lease program where money was deducted from their pay (7:12-7:27). Moving to Barry Farm required “a tremendous leap of faith and an absolute demonstration of rock solid courage” (7:53-8:00).

This was due to the dangers posed by hostile white attitudes and even violence from slaveholders

(

8:18-9:12). The Decline and Challenges Faced

Over time, the community faced significant challenges. The city was “incredibly cruel and mean” (9:27-9:28) to Hillsdale, including Barry Farm, leading to overcrowding and the construction ofpoorly maintained public housing (9:33-9:57).

Infrastructure developments like the Baltimore Railroad and I-295 cut off the community’s

access to the Anacostia River (10:57-11:33). This hindered their economic ventures like fishing and selling goods. The video states that “government encroachment” and “private business encroachment has eaten up the edges of Barry farm for highways and businesses”

(11:55-12:00). Community Spirit and Nostalgia

Despite the hardships, the early Barry Farm community was described as “beautiful”

(12:20-12:20). Residents recalled a time when “if you leave your back and front door open

nobody will walk in and steal anything” (12:32-12:38). Another thing to mention was that

neighbors were “just like family, they looked up to one another” (12:40-12:44), and it was a

“calm clean quiet community” (12:53-12:58).

There was a strong sense of unity and mutual support, with families communicating, working together, and participating in co-ops and youth activities (13:30-14:00). A former resident fondly remembers, “everybody was calling that’s my cousin or that’s my friend it’s my schoolmate and they confide in each other very well and I would love to see that again” (15:54-16:07).

Notable Figures and Their Impact

Solomon G. Brown (19:33-22:50), an incredibly influential figure from Barry Farm, born in

Washington D.C in 1829. He was a self-taught “renaissance man” (20:44-20:46), excelling in

poetry, natural science, biology, and geography.

Brown was a respected scientist and one of the longest-serving employees at the Smithsonian Institution. He also represented the community in the territorial government, elected by both Black and White residents. He was instrumental in bringing city services like sewers and water to the area.

One young resident expressed admiration, stating, “I would be like Solomon G Brown cuz

Solomon G Brown he came from like he came from nothing for real he came from like scratch”(22:06-22:12), highlighting his journey from poverty to prominence.

Frederick Douglass (23:59-26:50): Though he later moved to Cedar Hill, Frederick Douglass

and his family had a significant presence in Barry Farm. His sons, Charles and Frederick

Douglass, lived in the community since 1867 and were instrumental in its early organization. Charles Douglass became a School Board president, and Douglass Elementary School was named for him. The Douglasses’ involvement underscored the community’s prominence.

Samuel Edmonson (26:54-29:29): A key figure in the Pearl Escape, a significant slave escape attempt in 1848. Samuel Edmonson, from Barry Farm, played an integral role in planning andexecuting the escape, demonstrating immense courage and a fight for freedom. His story is seen as an example for young people seeking change in their lives (29:13-29:26).

General Howard and the Freedmen’s Bureau

General Howard was appointed by President Abraham Lincoln to lead the Freedmen’s Bureau(30:44-31:00). His role was to help resettle displaced people and educate newly freed men and women (31:51-32:05). Faced with immense opposition, Howard established a trust with SenatorPomeroy and hardware magnate Elvin to purchase the Barry Farm land (32:15-33:25).

A crucial aspect of this initiative was that the land was purchased by three African-American colleges (Howard and Lincoln mentioned), and the money from the sale and rental of lots went back to fund these institutions, including Howard University (33:55-35:10).

This “wonderful experiment” (35:11-35:12) also saw Howard establish Black educational

institutes throughout the South (35:16-35:24), leaving a lasting legacy of education for Black people (35:25-35:36).

Preserving the Legacy: A Disconnect with the Past

The documentary highlights a concerning “disconnect” between the current generation and the rich history of Barry Farm. Many young people living in Barry Farm today are “not even

connected with the fact that the soil that they’re living on was freemen soil” (16:36-16:41).

There’s a desire to advocate for developers to “Salvage this history” (18:41-18:45), but simply naming buildings after historical figures like Solomon G. Brown isn’t enough if the community doesn’t know their stories or their significance (19:26-19:32).

As one young person expressed, “I had to find him on the internet. I didn’t even learn about him in school. I wonder why he is not an out Tex” (22:49-22:54). The film implicitly calls for a reconnection with this vital past to inspire future generations.