My students Isabella (“Izzy”) Bradbury and Nadia Liban at American University have created two works of expressive art honoring“Atwai” (Deceased) Pochahsquinest Bassett, (1936-1968). Izzy created the multimedia collage piece “At Last!” and Nadia wrote a poem, “I can still see the stars.”

We hope this page will serve as a resource for others learning about MMIW/MMIP and for those interested in promoted art, poetry, and creative expression in support of the MMIW movement.

Background: During Fall semester 2025, students in both sections of my Race and Racism (Anth 210) course at AU have been working to assist the family of Atwai Bassett in reconstructing her life in Chicago, under conditions of Federal Relocation, until she went missing in late spring 1968. I have reviewed what we know of her life in a blog post, using her full name, and some of my students have created a website in her memory. Another student created a website reviewing the entire MMIW Movement. [Now that she has been properly re-interred back in the Yakama Nation, we are following tradition and not identifying her by her full name, but instead using the Ichiskin term “Atwai” (Deceased) for the time being.]

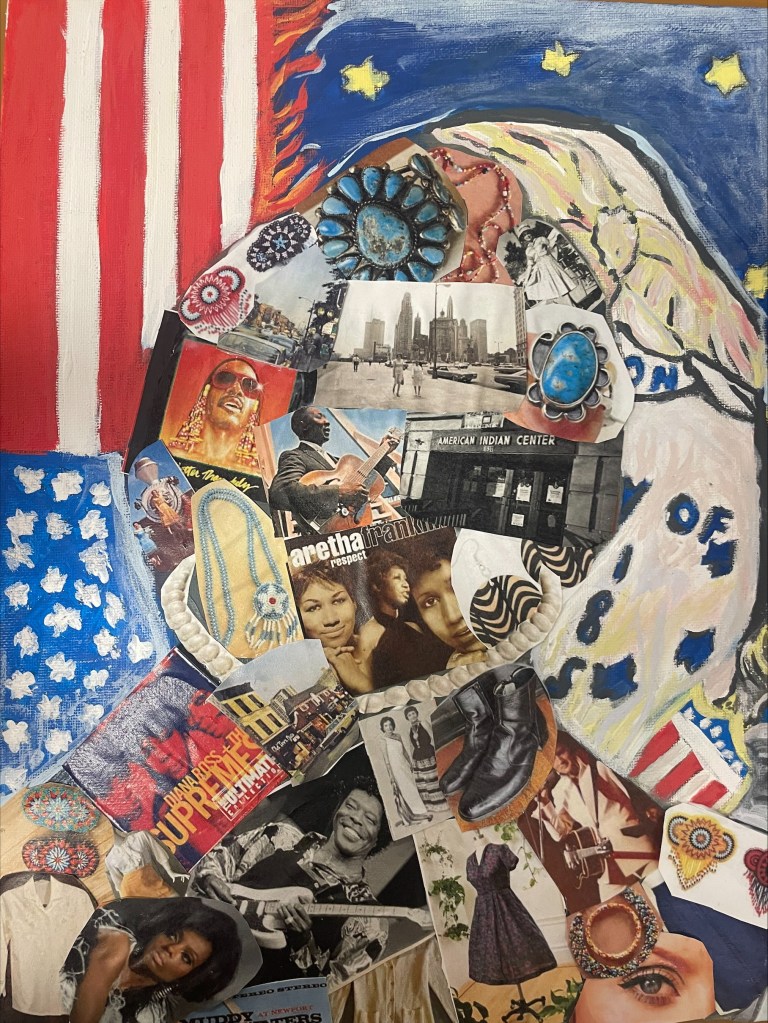

“At Last!” by Izzy Bradbury (a painting/collage)

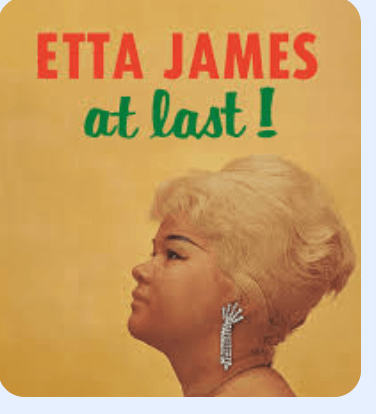

The title for the art work is ““At Last!” honoring the beloved song of the 1940s that became the signature song of American blues and soul artist Etta James. “At Last!” is also the title of Etta James’ debut studio album, released on Argo Records in November 1960. The album captures the incomparable energy of the city of Chicago on the eve of the 1960s. This is a song that the Atwai certainly would have heard living in Chicago and perhaps danced to. Hear the song at: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=1qJU8G7gR_g

The phrase, “At Last” also references our great relief that in September 2025, through the combined work of family members, MMIW researchers, and allies, Atwai at last came home to the land and people who cherish and hold her dear forever.

Visual description of art work: A silhouette outline of the Deceased is shown framed within the American flag and the Yakama Nation flag, which includes an Eagle sacred to the peoples of the Nation, as well as the outline of the state of Illinois, where Atwai lived from 1957 to 1968. Collage images within the outline of Atwai shows scenes from her imagined or reconstructed life in Chicago, including the skyline as it is seen from the Loop or Near North boulevards she often walked on, the American Indian Center that was just a few doors from her hotel in Uptown, some of the wonderful musical artists she might have encountered living on the South Side of Chicago, or heard on the airwaves, the kind of hip clothing including boots she might have worn, beaded work and Native American jewelry to honor her heritage and the Pan-Indian ideas that were emerging in Chicago on the eve of the Red Power movement.

Artist’s Statement: Though this art piece I seek to honor Atwai Bassett, humanizing her and exhibiting her interests in an artistic way. I used her ethnic identities as the background, American, Yakama Nation tribe, and one of Illinois; showing the broader context of her story. But Martha was more than that, as she had a life with hobbies, interests, and goals, which the public deserves to be more informed about. For the Bassett family, I wanted to make a physical representation of all that Martha had probably enjoyed being a young woman in Chicago. She is at the center of the art as a silhouette, her interests being the main focal point of the collage. (Izzy Bradbury)

A Talking Circle

Reflections by Students

Observations by Nadia: This piece immediately situates Martha Basset within a layered historical context, using the backgrounds of the American flag, Yamaka beadwork motifs, and Chicago’s skyline to visually map the intersecting identities she carried throughout her life. The collage mirrors the conditions caused by the Indian Relocation Act, a policy that pushed thousands of Native people–including young women like Martha–into urban centers with promises of opportunity without structural support from the government. The mixture of beadwork, cultural textiles, and city imagery shows that while she lived in Chicago, her Indigenous identity traveled with her, shaping her life in ways the public rarely acknowledges. In this sense the background becomes not just a setting, but a commentary on how policies were created to uproot families and place Native women into environments where they would become vulnerable.

The silhouette at the center, filled with music icons, fashion references, and a sense of everyday joy–is a refusal of the way Missing and Murdered Indigenous Women (MMIW) cases are often portrayed: reduced to statistics, stripped of humanity. Instead, Izzy fills Martha’s outline with items that feel lived-in, warm, and personal. These elements collectively remind the viewer that Martha was not just a victim, but a young woman with interests, tastes, and aspirations. In bringing the personal and the political together, the piece states that Martha’s story is not only a tragedy, but a statement to resilience, community, and the urgent need to remember her fully.

Observations by Can Yao: At Last!” made me feel the important role of art in memory and politics. The artist uses clipping, drawing and flag methods to present Atwai’s story before our eyes. A young girl with life and dance, dreams, hobbies, and a bright future.

This artwork really touched my heart. The various scenes inside, such as the city’s lights, music, culture, and clothing and accessories. These details can enable us to have a profound understanding of the girl Atwai. This girl who had vanished from history has been brought back to life by the work. A person with family, friends, and a future. On the other hand, the comments of Nadia and many scholars also resonated with me. It made me deeply realize once again that art is not merely a tool for commemoration. Instead, it can bring those who have been neglected back into the public eye once again.

Especially in today’s world where the MMIW/MMIP issue remains very serious, art can serve as a tool for us to speak out for justice. “At Last!” is not just about the past, but also about the future: Atwai has finally “returned home”, but this journey home also reminds us of that memory, respect, and action must all continue.

Observation by Hiba Irmak Kir (Class TA): This artwork offers a compelling reflection of what we currently know about “Atwai” Bassett, even though many aspects of her story remain unknown. The collage—bringing together the cultural landscape of the 1960s along with racial and national symbols, highlights the fragmented nature of American socio-political life. While a sense of coherence is often projected through top-down political narratives, Atwai’s life and cultural engagements reveal the fragmentation and ambivalence of American ideals as experienced from below. Her life stands as powerful evidence of the significance of Indian American heritage and its intersections with African American and gendered forms of resistance to entrenched structures of power.

Reflections by Family, Friends, and Allies:

–Emily Washines (Yakama Nation, MMIW advocate): Having artistic expression for our MMIW is a part of helping bring awareness as well as processing the life and events of those we’ve lost.

Januwa Moja (DC artist, community advocate): To the students who worked on this project (MMIW) Sometimes you have to take a chance and follow your heart to give voice to the voiceless. The collage that was created did just that. You shined a light on a topic that has gone dormant in the mainstream. May you continue to use your art as an opportunity to speak your truths and stand in your power.

Glenna Cole Allee (artist, San Francisco, glennacoleallee.net): My gaze is led around the collage by the painted areas that overarch it. I notice that the edge of the painted flag is in tatters… or is it on fire? And the stars upon the flag have become like flowers. They contrast with the golden stars sparkling in the dark blue sky.

The collage, partially framed by the painted areas, has many elements of an alter: images that evoke personal possessions, turquoise, beads, and styling clothing that Atwai Basset may have treasured in her time, and music she may have moved through life to. But these elements seem caught up in a wavelike, turbulent sense of motion, rather than still and as they would be if posed upon an alter. This momentum suggests that Atwai Basset’s life was caught up and carried by tumultuous forces.

The collage does also feel like a portrait: animate, as if some watchful spirit is behind all of those bits and pieces. For me this makes it very moving; it is an evocative work, in the truest sense.

—Ellen Schattschneider (Anthropologist, Brandeis University, Emerita) writes: I greatly appreciate the interplay of printed images (some of which are partly familiar) and drawn lines, textile surfaces, all framed by what I see as a human shape/torso that seems to hold all of this in its embrace. The turquoise jewelry “eyes” give the figure an animating depth, leading the view to expect this person will soon have something to say. This figure is simultaneously intensely private, while at the same time being fully engaged in larger public historical moments–thank you for thisdeeply evocative image!

–Jean Comaroff (Anthropologist, Harvard University, Emerita): As somebody once myself drawn to seek my fortune in Chicago, I was deeply moved by this montage, by its juxtaposition of intimate objects, vibrant culture, and urban emptiness. It suggests a place where migrants realize rich possibilities but can also fall victim to failure and alienation; a place of hope, and sometimes of despair. At a time when the city’s migrants have become prey to new forms of violence and disappearance, this work reassures us that there are those watching who will never look away or forget.

– Debbora Battaglia, (Professor Emeritus of Anthropology and Research Associate, The Smithsonian National Museum of Natural History.): I am deeply moved by the energy of recovery that powers this beautiful painting and rings so truly through the poem. Mutually augmenting, that pulsing of image and text is the creative armature of hope for a future of resounding empathy, for Atwai Bassett as for all who are living in vulnerability, undefeated.

Poem by Nadia Liban

I can still see the stars

I left the river and the hills behind,

the cedar scent still clinging to my sleeves,

my mother’s voice is humming somewhere in my bones.

The city came to me with its promises,

its music pouring from open windows

its people moving fast enough to make me believe I could move with them.

Some days I almost do.

There is a rhythm this city beats to.

In the markets, in the sidewalks, in the way the sun slips between tall buildings

or the force of the chilling winds searching for someone it remembers.

I learn new songs on borrowed radios, dance in borrowed rooms,

find pieces of myself stitched to sounds

I didn’t grow up with but still recognize.

I am not a stranger everywhere.

At night, I trace the constellations I remember,

the same ones my mother taught me–

her hand warm around mine,

guiding my finger across the sky

as if she could draw a future there.

The world is big enough to hold everything I was and everything I’m trying to be.

Sometimes a drumbeat finds me–

In passing cars, in upstairs apartments,

in the steady pulse of my own heart.

Then I know:

I am not lost, not broken, not alone.

My story is still breathing,

Woven from mountains and sidewalks,

from old socks and new dreams–

a life larger than fear, than distance,

large enough to shine.

Poet’s Statement (by Nadia Liban) : This piece is meant to humanize Martha’s life through her possible point of view. It explores the in-between of leaving home and finding belonging in a new place. I try to imagine the emotions a young Indigenous woman like Martha might have carried while she navigates a new city. Rather than focus on loss, the piece centers memory, identity, and the small moments—like a mother guiding a child’s hand toward the stars—that continue to anchor someone even far from home. It blends nostalgia with hope, honoring her humanity through the textures of everyday life.