This weekend (November 21-23) the Umbrella Art Fair (International Square, 1850 K Street, NW Washington DC) features a dazzling installation presented by the Capital Hill Boys Club Intergenerational Gallery. The project emerges out of the celebrated National Gallery of Art exhibition, Afro Atlantic Histories, April 10 – July 17, 2022

https://www.nga.gov/exhibitions/afro-atlantic-histories which originated in a major show at the Museu de Arte de São Paulo and the Instituto Tomie Ohtake in Brazil in 2018, incorporating 130 art works from across four centuries of the African Diaspora.

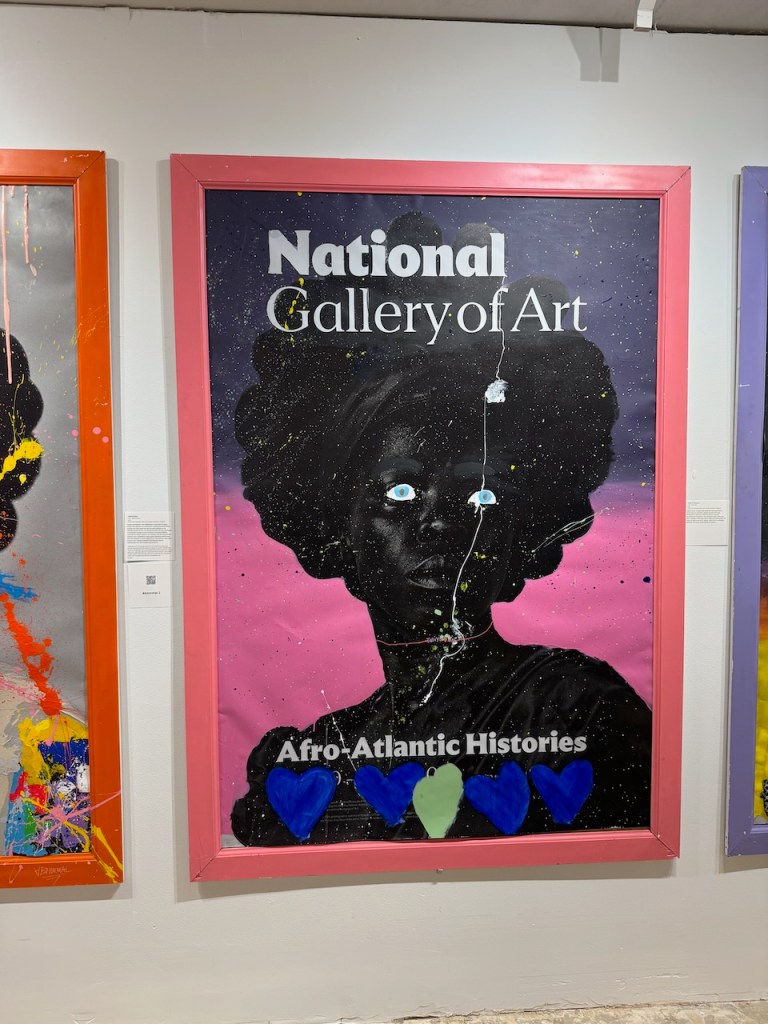

The exhibition poster feature Zanele Muholi’s Ntozakhe II (Parktown) a striking image of the artist in blackface with an elaborate wig and head-tie, eyes slightly raised. Large format versions of the poster burst upon DC public spaces through the Metro public transit system. At the conclusion of the show, nine of these posters were presented by the National Gallery to the CHBC Gallery, allowing for collaborative projects between professional artists and local schoolchildren, honoring Muholi’s original work through acts of artistic intervention and reinterpretation.The series was first presented in June 2024 at the CHBC Gallery at 16th and Marion Barry, SE (Anacostia, Ward 8_, and is now on view at the Umbrella Art fair.

The original image, Ntozakhe II (Parktown), is part of Muholi’s photographic series of digitally altered self-portraits “Somnyama Ngonyama” (translated by the artist as “Hail, the Dark Lioness”), The projects consists of carefully posed images taken in locations around the world, through which the artist-activist gives voice to a vast number of black South Africans, primarily LGBTQ, regularly consigned by dominant social institutions to the shadows. (I have previously written about the overall project and its evocation of Nguni royal praise poetry at:

https://markauslander.com/2021/10/30/panegyric-imagery-in-zanele-muholis-somnyama-ngonyama/

The artist has remarked that Ntozakhe II (Parktown) is inspired in part by the Statue of Liberty, a work famously presented to the United States by the people of France in honor of Emancipation, later re-conceptualized as a celebration of immigration. Like other images in the “Somnyama Ngonyama” series,the work plays creatively and critically with a long history of colonial blackface and minstrelry, reclaiming a proud and defiant stance of Black feminine and queer subject positions. Other works in the Somnyama Ngonyama series, most notably those titled “Bester” honor Muholi’s mother, who worked as a domestic laborer. It is possible that a trace of his maternal figure informs Ntozakhe as well. The name Ntozakhe, in isiXhosa and isiZulu can be translated as “One who comes with their own belongings,” suggesting a proud lineage that will result in significant inheritance.

Proceeding left to right, the first remixed work in the project is Untitled, by Brian Bailey Jr. Over 20 abstract forms, of varying colors, cover the subject’s face, although Zanele’s striking eyes remain visible. I have the strong sense of the swirling energies of a rotating Yoruba Egungun mask in performance, sequined and mirrored cloth trips rising in rotation, cycling the flows of ancestral power and the invisible world into the domain of the Living.

Bailey may have drawn particular inspiration from one of the most striking works in the 2022 exhibition, Daniel Lind-Ramos’s Figura de Poder (2016–2020) created from found materials of the Afro-Puerto Rican community in Loíza, northeastern Puerto Rico. The work itself does appear to evoke Egungun shapes, consistent with the Ogun festival and other Yoruba-inflected performances.

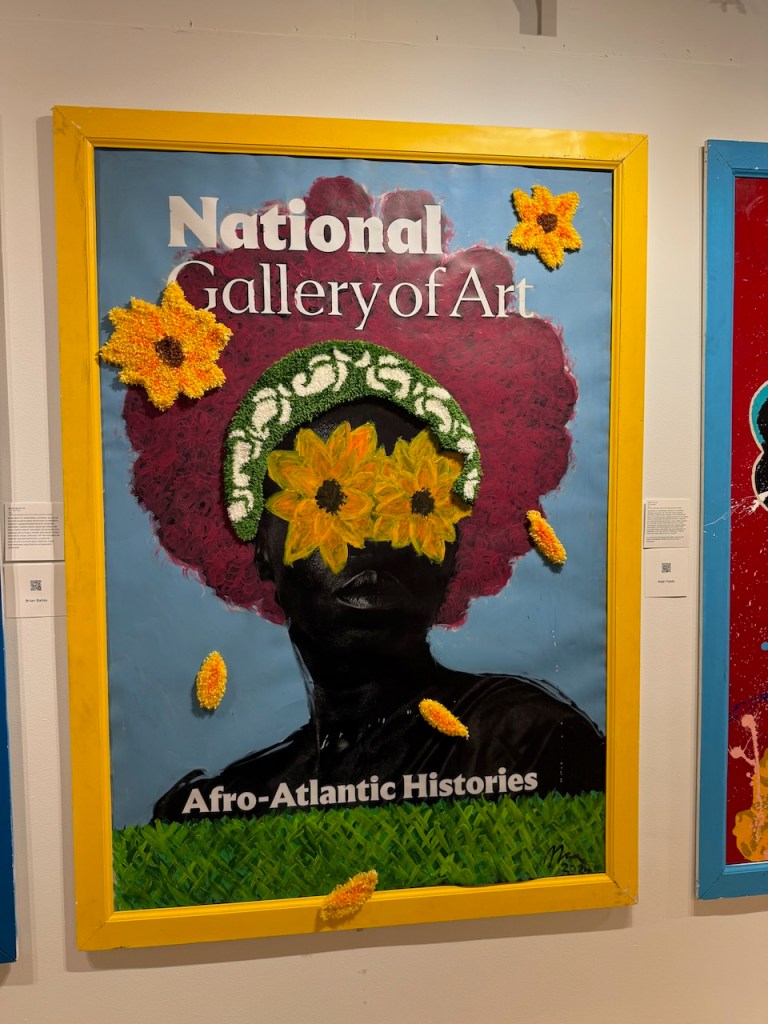

The second reworked poster, “Bloom,” by Naje Fields, may be in conversation with the CHBC mural “Bloom” by Nonie Dope, which transforms bullet holes into blooming flowers. Fields’ interpolations incorporates raised upholstered pieces, including a green swatch across the forehead and floral designs that, like Dope’s imagery, seem to replace bullet holes with signifiers of new life. The net effect, my students thought, was akin to a flowering bush or tree, promising renewed growth emerging out of sites of violence and trauma.

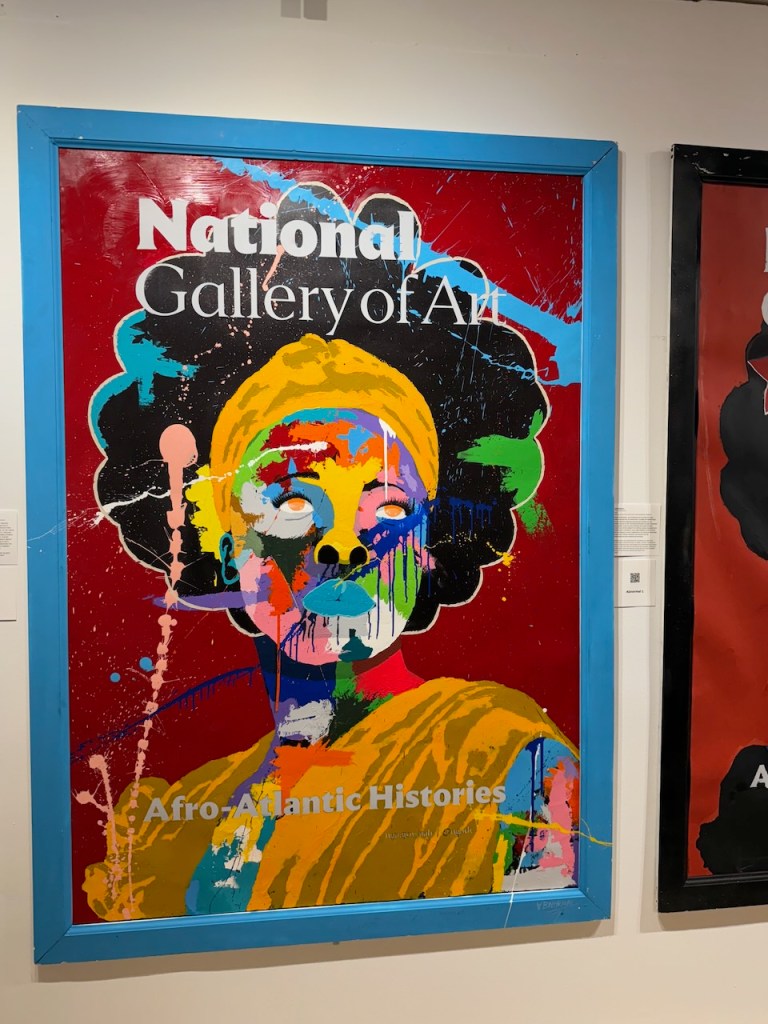

The third poster, one of two by Abdul Brown in the installation, energetically splatters multiple hues across the face, a queer-friendly celebration of the Rainbow Nation, with blue lips, and a bright yellowed head tie. The toga, subdued in the original monochrome image, is now covered in rich rivulets of color. The Afro largely retains its blackness, outlined in yellow, with swatches of blue and green. A bolt of blue crosses diagonally above the head, from the blue frame’s top to its right edge.

The fourth, by students Tamara Mceachin and Tyrone Graves, plays on the design of the Stars and Stripes, an acknowledgement of the original image’s citation of the Statue of Liberty. One white star hangs us a kind of earring, while white and red stars adorn the voluminous hair. Simple lines of red, white and blue describe basic features of the face and the folds of the toga. The net effect is to re-inscribe forcefully the presence of Blackness at the heart of the American experiment.

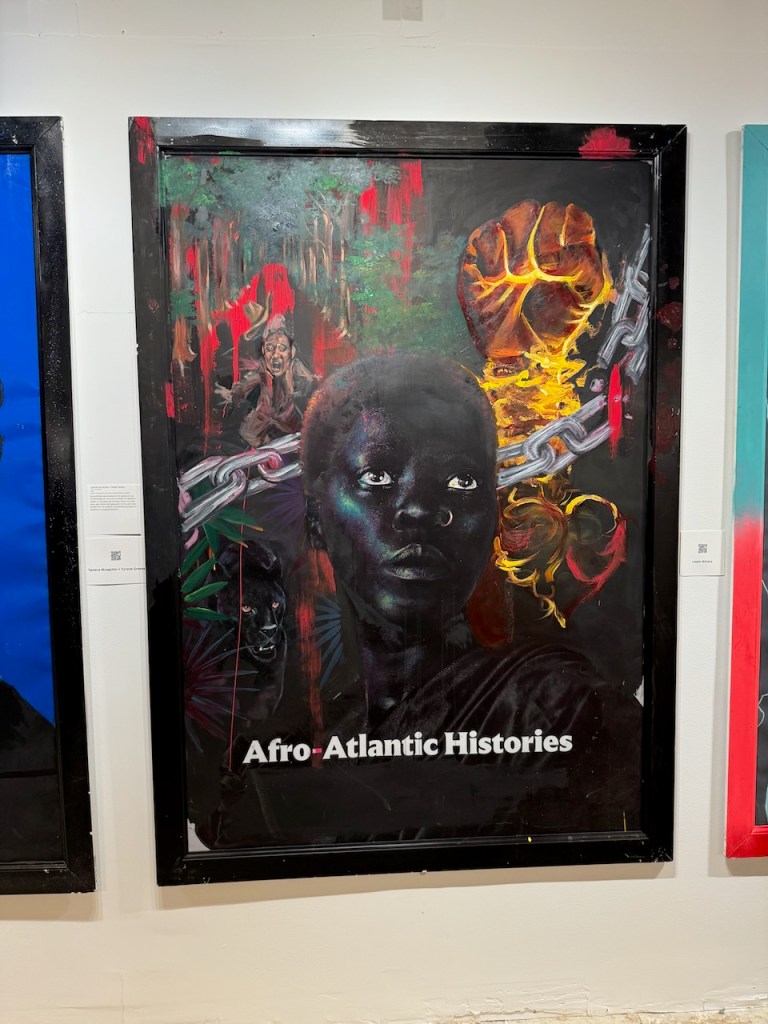

The fifth poster, by Lewis Waters, reworks Muholi’s head to render her skull fully shaven, a classical image of Black beauty. In the lower left, emerging out of a green forest, we we glimpse the burning eyes of a Black Panther, a kind of doppelganger of the Muholi head that seems to recall a noble African heritage. Behind the head is a silver linked chain evocative of the history of the slave trade and enslavement; the chain appears to be broken in the upper right by a red swatch, perhaps evocative of the blood of cleansing revolutionary violence. Emerging from this broken link is red and yellow mass reminiscent of fire coalesced into a huge clenched fist, another homage to revolutionary histories. In the upper left, we glimpse a white man, perhaps an enslaver or a perpetrator of another sort, racing in horror towards the self-liberating Black woman, his stetson flying off his head. The enslaver is surrounded by dripping patches of red, recalling, presumably, the blood shed in colonialism and the Middle Passage. We glimpse, perhaps, a trajectory from the Underground Railroad through continuing struggles for liberation.

The sixth poster is by gallery co-director Mark Garrett and his student Jazlyn Brown. My students read the image as homage to the Marvel super-heroine Storm or Ororo Monroe, a high-level mutant member of the X-Men, a descendant of African priestesses who controls the weather and who for a time was consort of the Black Panther of Wakanda. Here, she wears a metal collar and a kind of metal armature, which could be read as instruments of enslavement, but which here seem to be conductors that condense bolts of lightning from the sky. Her Black face is framed by triangles of red and green, symbolic of the black, red and green of pan-Africanism. Perhaps her body functions as an enormous cosmic battery, pulling in the voltages of the cosmos and then shooting out through her eyes laser-like towers of light into the heavens. Her eyes are obscured, but one senses she possesses supernatural vision, seeing far beyond conventional powers of sight, far into outer space.

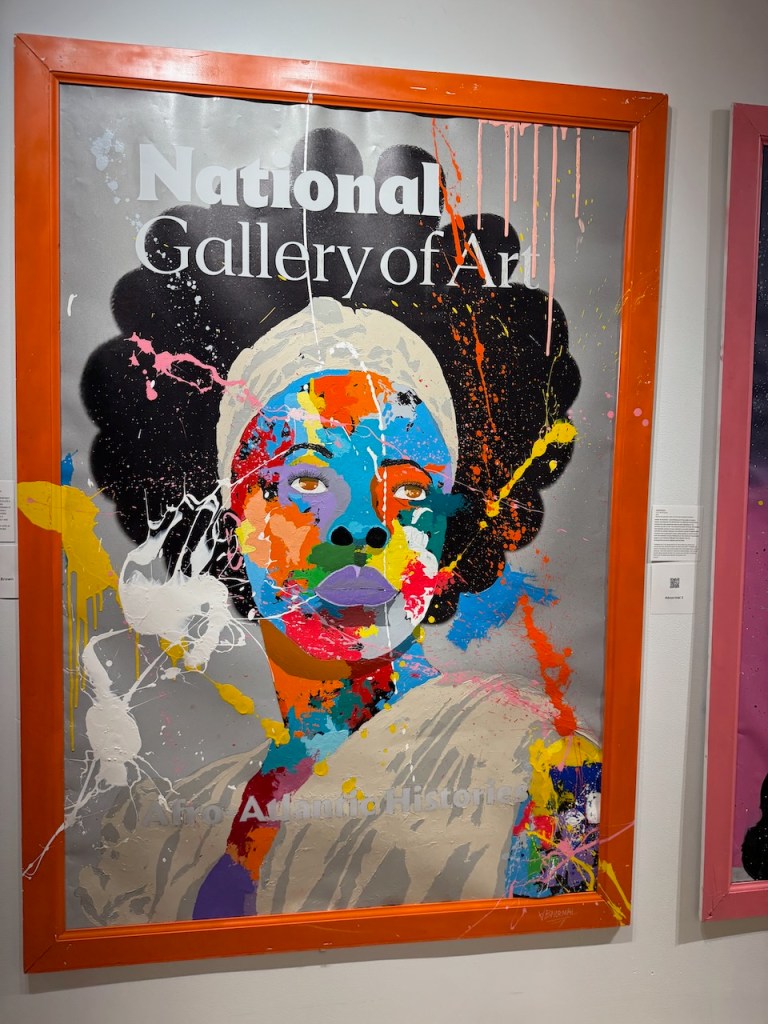

The seventh image is again by Abdul Brown, filled his signature multicolored aesthetic of exuberant swaths of paint blotches and dripping patterns. Again, one senses the revelation of an overpowering aura radiating off the figure’s face. The head wrap is prominently in white and the capacious afro remains in black, with multicolored filaments of paint dripped across.

The eighth image, by Taniya Graves, moves us dramatically into an Afrofuturist frame. The blackness of Zanele’s face and body become the night sky of the universe, filled with stars and swirling galaxies. The symmetrical white eyes of the face are juxtaposed with an off-center white blue splotch that might evoke the Magellanic Cloud, the brightest objects of the southern hemisphere sky. A white drizzled line, an evident home to Abdul Brown’s signature drip style, bisects the cloud and traverses the figure from the “L” of the upper word “National” down to the base of the figure’s neck. Five hearts adorn the woman’s torso, perhaps evocative of the power of love that permeates the Afrocentric universe.

Afrofuturist mythology is further developed in the series’ final, ninth remade poster, by gallery co-director William Dietrich, titled, “Mapping Like She Freed the Slaves”. The heroine now wears an “X” patch, further suggesting, as in the sixth poster, membership in the X-Men league of supernatural mutants. Her lower half is silhouetted by bands of yellow and red, suggestive perhaps of a sunset that is about to give way to the cosmic mysteries of the night sky. Her head-tie is a collage made out of torn, reassembled images from early comic books that celebrate, like image six the magical X-mutant Storm. One has the sense of concentrated consciousness, the power of Black Mind that explodes outwards into the aurora borealis, shimmering fireworks of greens, reds, and yellow that illuminate the firmament in the splendor of the northern lights.

Taken together the series of nine remixes takes us on an extraordinary journey, enabled by the gift of Zanele Muholi’s singular gift and the generosity of the National Gallery team. The CHBC team’s commitment to collaborative partnership, binding established and emerging adult artists with high-schoolers, speaks to a profound commitment to generational continuity. In that sense, the project embodies the central spirit of the Nguni concept of “Ntozakhe”, the title of the founding, repeated image. As noted, naming a newborn “Ntozakhe” signifies that the child will in time be bequeathed a great inheritance, worthy of their substantial lineage. Similarly, the gallery’s co-directors and resident artists seek to bequeath to their posterity gifts of artistic inspiration, to travel throughout the generations forever. In the shadow of the forces of racial capitalism, that have for centuries sought to corrode lines of social continuity in the Black community, the whole project is a stunning performance of revitalized lineage- from the ancestors to their posterity.

The curatorial decision to start the installation with the swirling enigmatic Afrocentric energies of the Brian Bailey Jr iteration, I would suggest, can be read as a kind of invocation of the muses, that launches us into this dreamlike pilgrimage through history, time, and space. We plunge into the violence and healing struggles of the Black American experience, with glimpses of the Middle Passage, the Underground Railroad, and the contemporary scourge of gun violence. All this proceeds under and through the watchful eyes of the Statue of Liberty, an ambiguous signifier of the promise of freedom so long denied to Black America. Out of this tumultuous history enters the magicality of Africa-informed superheroes, illuminating the far reaches of the universe. In the final images, the series explodes into vast cosmos of the future. Into this ever-expanding skyscape, the luminous figures that Jim Chuchu terms the “Afronauts”— oscillating between the ancient ancestors and their distant descendants—go traveling.

It is my deepest hope that this incomparable series can be preserved as a whole in an institutional collection, so that future generations can travel, following Zanele’s footsteps along this stellar road of Black beauty and incandescent light.