What do we know of the Peggy, the slave ship that transported 144 enslaved Africans from The Windward Coast in West Africa in 1770, evidently selling scores of them in the port of Georgetown, Prince George’s County, Maryland, which three decades later became part of the District of Columbia?

It would appear that the Peggy is the first ship documented to have directly sold slaves in Georgetown, so its story is of considerable historical interest. (References to this sale include Johnston 2021)

It should be noted that some sources (eg Keyes Port) have misread data compiled in Slave Voyages: the Trans Atlantic slave database, slavevoyages.org, to conclude that enslaved people were landed in Georgetown for sale much earlier, from at least 1732 onwards. This is improbable, since the town of “George” or “George-town” was not even laid out until 1751. The principal mistake appears to be misreading the destination “North Potomac” as meaning Georgetown, whereas “North Potomac” simply seems to be a designation for the north bank of the Potomac river, stretching about 100 miles from the river’s mouth on the Chesapeake Bay to the Fall line, near the modern day site of Georgetown. Generally speaking, the voyages that terminated in “North Potomac” seem to have landed many miles downriver of the present day site of Georgetown, in Charles County or St Mary’s County, Maryland

Note: Testimony entered into the Congressional Record by Rep. Eleanor Holmes Norton (October 5, 2021) asserts that “The first enslaved Africans were believed to have been brought through the Georgetown port in 1732.” The voyages referenced in this account disembarked enslaved captives in “North Potomac” ports, but there is no direct evidence so far as I know that the Georgetown port recieved slave ships prior to the 1770 sale from the Peggy.

The August 1770 Sales

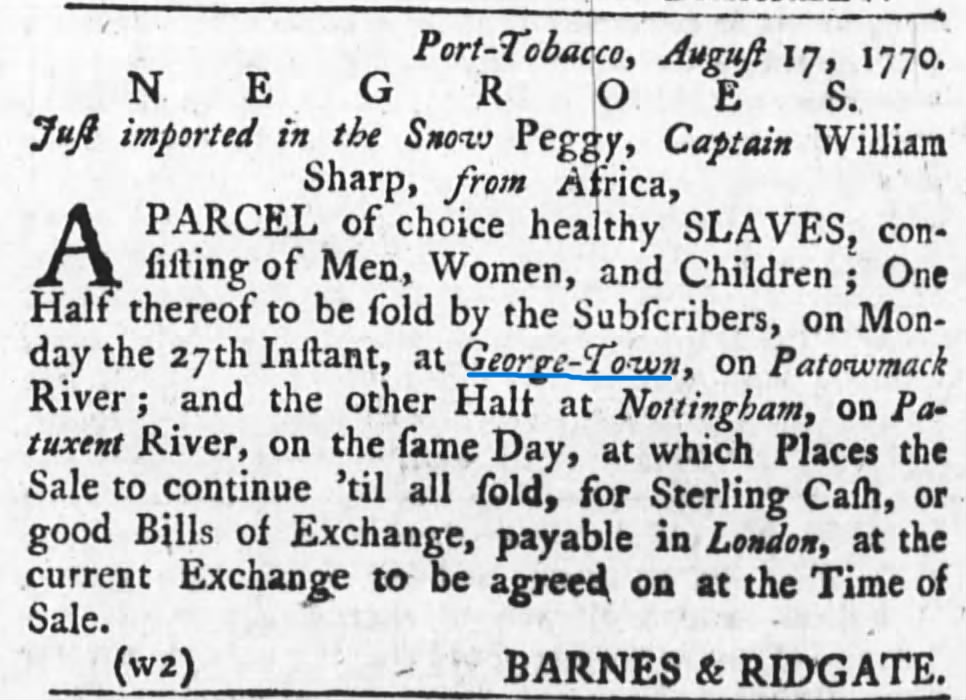

Our principal record of the 1770 sale from the Peggy is from an advertisement in the Maryland Gazette on August 30, 1770, placed August 17, referring to a double sale that was to take place on August 27, 1770. The notice reads:

“Port Tobacco , August 17, 1770. NEGROES. Just imported in the Snow Peggy, Captain William Sharp, from Africa,

A PARCEL of choice healthy SLAVES, consisting of Men, Women, and Children; One Half thereof to be sold by the Subscribers, on Monday the 27th Instant, at George-Town, on Patowmack River; and the other Half at Nottingham, on Patuxent River, on the same Day, at which Places the Sale to continue ’til all sold, for Sterling Cash, or good Bills of Exchange, payable in London.”

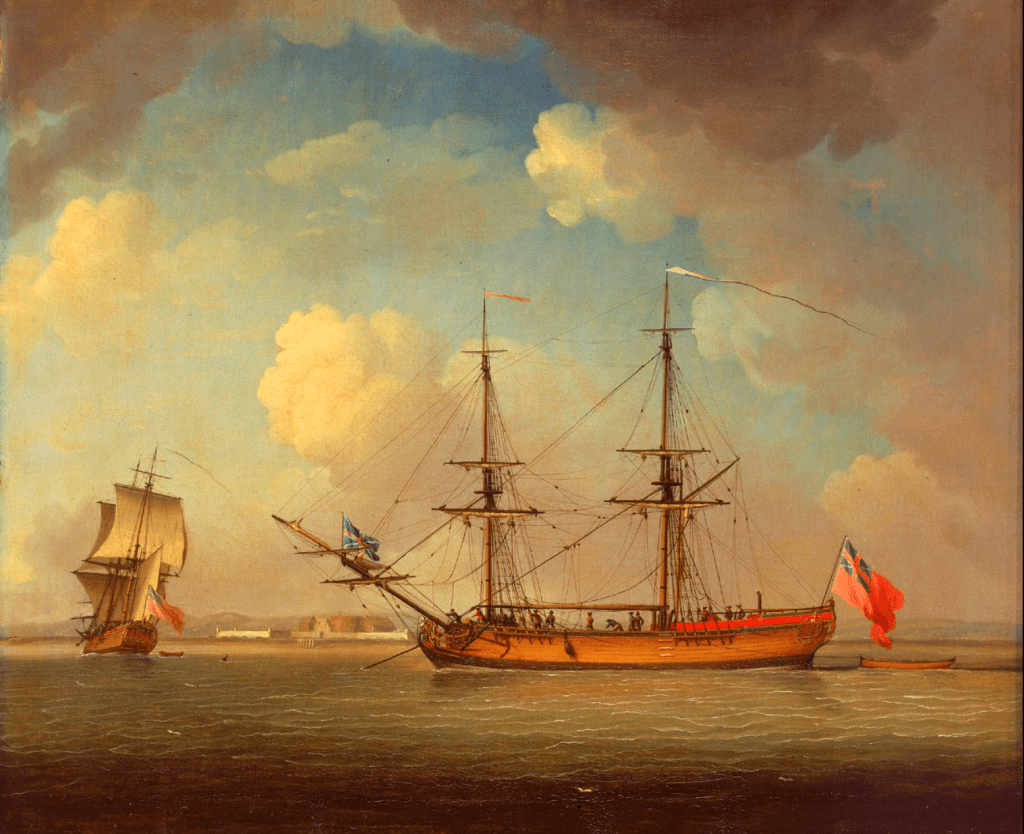

Note that the term “snow” is derived from the Dutch word, “snauw” (beak) referencing the distinctively shaped prow of a two masted vessel with a larger rear triangular sail. Hence, the vesssel was named the “Peggy”, not, as in some published accounts on line, the “Snow Peggy.”

National Maritime Museum, Greenwich, London.

The Trans Atlantic Slave Trade database assigns the 1770 trip of the Peggy the unique voyage ID #91463, and records the Peggy was constructed in Liverpool in 1768. The Peggy under Captain William Sharp undertook two previous slave voyages prior to its journeyto Maryland in 1770. In 1768, it took on slaves in Bassa (in present day Liberia) and disembarked them on the island of Dominica, and in 1769, it collected slaves at Grand Sestos (present day Liberia) on the Windward Coast, and again disembarked them in Dominica. The 1770 trip to Maryland would thus appear to the Peggy’s first trip to mainland North America,

The Peggy departed Liverpool, on August 8, 1769 then collected 166 slaves from locations on Africa’s “Windward Coast” (the region between Cape Mount and the Assini River, which encompassed parts of modern-day Sierra Leone, Liberia, and Côte d’Ivoire, known as the “Windward Coast” since ocean-going vessels traveling south regularly encountered winds directly blowing into them ) After crossing the Atlantic, the Peggy disembarked an unspecified number of slaves on the island of Dominica, possibly in June, then traveled about 1,800 mile northwest to Maryland, where it sold the majority of its human cargo in August 1770.

Reading the wording of the advertisement, we may infer one scenario: upon arriving in the Tidewater region the Peggy first deposited half of its enslaved people in Nottingham, which at that point was located at a point on the Patuxent river still navigable by ocean-going vessels. Then the Peggy might have sailed down the Patuxent to the Chesapeake Bay and sailed about 100 miles up the Potomac to the port of Georgetown, to disembark the remaining slaves in its cargo. Speculatively, if around 45 slaves were sold in Dominica, then perhaps about 50 were disembarked in Nottingham and about 50 disembarked in Georgetown. (As of this writing, I have not found specific records of how many slaves were sold at any given location or details on pricing or names of those sold.)

Georgetown port, as noted, is situated just below the Fall line, marked by rapids to this day, that rendered it the furthest navigable site up the Potomac River for ocean-going vessels. (For this reason George Washington and others campaigned to organize a canal to open up more of the interior to trade and other mercantile activity.)

Barnes & Ridgate

The firm that organized the slave sale, Barnes & Ridgate, was a partnership of John Barnes and Thomas How (or Howe) Ridgate, based in Port Tobacco (Charlestown), Charles County. Maryland, headquartered in Stagg Hall, which still stands. They were primarily tobacco merchants, with real estate holdings in multiple Maryland locations. It is not clear why Barnes & Ridgate chose to hold two simultaneous slave sales in Nottingham and Georgetown; perhaps they calculated that better profits could be realized by appealing to two geographically distinct clientele, one in the upper Potomac Georgetown region, marked by relatively modest agrarian holdings and mercantile firms, and the other around Upper Marlborough, an area of dense slave-based plantations.

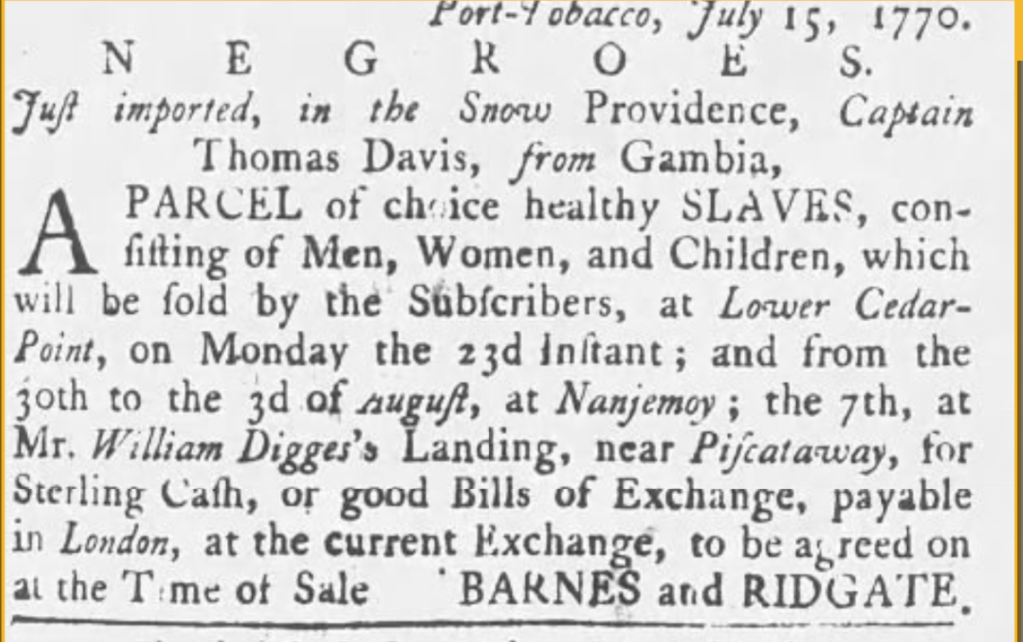

A few weeks before the Georgetown and Nottingham sales of the Peggy’s human cargo, Barnes & Ridgate advertised the sale of another group of slaves from the ship Providence, also a “snow” vessel, captained by Thomas Davis and owned by a Mr Shoolbrd, These slaves, purchased in Gambia, were to be sold at Lower Cedar Point, on July 23, from July 30 to August 3, 1760 at Najemoy and on August 7 at Mr William DIgge’s landing near Piscataway. (slavevoyages.org records that on this voyage the Providence embarked 162 slaves in Gambia and disembarked 132, thirty captives presumably dying during the horrific passage.)

It is not precisely clear how Barnes & Ridgate came to organize these various sales from the Providence and the Peggy. They are not listed as owners of the Peggy, which was owned by Peter Baker, Robert Green, John Clarke and John Johnson, whom were I presume were Liverpool merchants.

It is possible that Barnes and Ridgate’s key link to the owners or captain of the Peggy was through the wealthy merchant Abraham Barnes, father of John Barnes. Abraham Barnes, with James Gildart, was co-owner of three documented slave trade voyages: the Upton which in 1759 transported slaves from Gambia, landing 205 slaves in Annapolis, Maryland on August 8, 1759; a later trip by the Upton, carrying about 137 slaves from Gambia to the port of Nanjamoy in Charles County, Marylnd in 1761; and the Lawrell, which purchased slaves at James Fort in Gambia. (The subsequent fate of the Lawrell and its slaves is unknown.)

Whatever profits Barnes and Ridgate may have realized from these slave sales, they quickly ran into major financial challenges, during the British debt crisis of the early 1770s which caused widespread hardship for the mercantile and planer elite in the thirteen colonies. In May and June 1773, trustees for Barnes and Ridgate advertised for all those indebted to the firm to settle their debts. The Fall of 1773 saw several urgent sales of real estate and mercantile goods by the firm, and multiple calls by trustees to settle the firm’s extensive debts. By the time of his death in 1773, the father of John Barnes, Abraham Barnes, a major landowner and enslaver, had lost patience with his son’s business misadventures. Abraham Barnes’ will, dated June 29, 1773 states:

“In 1764 I gave my son John a very sufficient quantity of goods to begin trade and merchandise. Contrary to my expectations, he has carelessly lost and sunk all I gave him and is more in debt than I am able to pay, he having stripped all the ready money I had and has involved me in a very considerable security to Osgood, Hanberry and Company, merchants in London, and others. On the whole, this will amount to an equal share of my estate, but above all, he has robbed me of my happiness and peace of mind at a time of life when I expected to be free from any disturbance or anxiety.

When he reflects on this and that this profoundly unhappy condition and misfortune is entirely owing to his own obstinacy in rejecting my advice and opinion in all things and at the same time not informing himself of the true state of his affairs and endeavors (and) to keep everything material from my knowledge. From this melancholy consideration, he cannot, with any reason, expect any further favor or indulgence from me. Therefore, I give all to my son, Richard Barnes”.

SOURCE https://reno.stmaryshistory.org/smc/articles_files/july_ABarnes.html

John Barnes appears to have been in considerable financial distress for the rest of his life. He moved to property owned by his brother Richard, who as noted above was the sole beneficiary of their father Abraham’s estate. John Barnes died in Washington County, Maryland in 1800. [Richard Barnes, who died in 1804, attempted in his will to free approximately 200 of slaves; due to legal technicalities only 101 of this number attained freedom.]

Thomas Ridgate, the other partner in Barnes and Ridgate. also seems to have been consumed with debt challenges in his final years. He died intestate in Charles County in March 1790 in Charles County, Maryland. His court ordered estate inventory lists 13 enslaved people: Abram, 33 years old old, Jess, 31, Sam 19, (subject to convulsive tfits ) Frederick 5, Spencer 2, Fanny, 24, Nell 17, Jane Sickley, 15, Molly 16, Darkey, 7, Milly 5, Monaky, 2, Priss, 7. Of these, Abram, Jess and Fanny were old enough to have come off of the Peggy, although that does seem unlikely.

Captain William Sharp and the Peggy: The Robins Johns episode

William Sharp, who captained the Peggy into Georgetown in 1770? is recorded as have captained two later slave trading voyages on the Peggy. In 1772 (Voyage #91741) he sailed from Liverpool to the Windward Coast and then disembarked 287 slaves in Dominica. By the time of this voyage, he had evidently earned sufficient funds to be listed as a co-owner of the voyage. In 1774, Sharp again captained (with George McMein) the Peggy (Voyage # 91906) from Liverpool to the Windward Coast, then disembarking slaves in British Honduras and Charleston, South Carolina

In his fascinating book, The Two Princes of Calabar (2009), Randy Sparks infers that Captain Sharp intersected with one of the most intriguing episodes in the history of the Atlantic slave trade, the story of Little Ephraim Robin John and Ancona Robin John, known as the Robin Johns or “the two princes,” The Robins John, who may have been uncle and nephew, were prominent Efik slave traders in Old Calabar (present day Nigeria), who were captured, sold into slavery and transported to Dominica. Sparks proposes that in Dominica they made contact with Captain Sharp, who falsely promised to return them to Old Calabar, but who in fact tricked them, transporting them to Virginia and selling them to the Bristol-native Captain John Thompson, who abused them seriously. With great difficulty the Robin Johns eventually secured their freedom and returned to Old Calabar. Sharp clearly had connections with the Efik slave traders: Sparks notes that the Efik ruler of Calabar, Grandy King George, the brother of Little Ephraim, praised William Sharpe in a letter in 1773, as a “very good” man, not knowing how Sharp had tricked his brother and nephew (Sparks 2009, p 168, fn 19)

(I am having difficulty retracing all of Sparks’ detective work, since the journey of the Peggy he references, #91357, is not listed in slavevoyages.org as continuing to Virginia, although of course it may have done so. Alternately the Robin Johns may have been on the Peggy voyage to Maryland and purchased by Captain Thompson in 1770.)

This Captain William Sharp may be the same William Sharp who two decades later in 1792 is listed as owning 58 slaves in St Ann’s Province, Jamaica.

It is my hope that future research will reveal more details on the lives of the persons transported on board the Peggy and sold in Georgetown in August 1770.

References

James H. Johnston. Slavery was part and parcel of the wealth of early Georgetown.Washington Post. August 27, 2021. https://www.washingtonpost.com/opinions/2021/08/27/slavery-was-part-parcel-wealth-early-georgetown/

Sparks, Randy J. (2009). The two princes of Calabar: an eighteenth-century Atlantic odyssey. Harvard University Press

Keyes Port of Washington: Capital City Slavery Tour,

John Barnes, legal records; from https://www.colonial-settlers-md-va.us/getperson.php?personID=I102445&tree=Tree1&sitever=mobile