In a previous post I mentioned the enslaved man Tom, who escaped from merchant Robert Peter of Georgetown on October 4, 1761.

On October 9, 1761 Peter placed the following advertisement in the Maryland Gazette

“Rock Creek October 9, 1761. Ran away from the Subscriber in the 4th instant, a very likely Negro Fellow named Tom, about 22 years of age, 5 feet 8 inches high, was imported from Africa 2 1/2 years ago, but speaks tolerable good English, tho’ slow, and appears bashful. He had on when when he went away, an over Jacket of dyed Cotton, and under Jacket of plading, an Osnabirg Shirt and trowsers; it is imagined that he carried with him some spare shirts and trowsers, and also some Bed Cloathes, and as we miss a Canoe from this shore, it is expected that he has gone by Water, especially as he was used to Water for a least a year before I purchased him, and had in that time made an attempt to get to sea in an open Boat.

Whoever apprehends the said Negro and secure him so that I can have him again, shall be paid the sum of Twenty shillings, if taken with ten miles of this place, thirty shillings if twenty miles, forthy shifllings if thirty miles, fifty shillings if forty miles an Three Pounds if at a greater distance by Robert Peter”

Several points are worth noting. If Tom was 22 years old in 1761, he would have been born around 1739, presumably somewhere in West Africa. As noted previously, this period, two and half years before October 1761 might correspond with the time frame, roughly August 1759, when three slave ships sold their human cargo in the environs; the True Blue from the Gold Coast, which sold slaves at Nanjemoy, Maryland; the Venus with slaves from the Gambia, which sold slaves at the naval station at Cedar Point; (both locations in southwestern Charles County, Maryland) and the Upton, with slaves from Gambia, which sold slaves in Annapolis. Tom might have been imported on any of these vessels.

Tom had at least one previous master before Peter purchased him, and had been familiar with the water, perhaps as a fisher or a ferryman. The shad run and other fisheries on the Potomac were highly profitable and many enslaved people were put to work exploiting these valued riparian resources. Tom had, Peter says, once before tried to escape to sea on an open boat, which suggests he had considerable courage and some nautical skill,

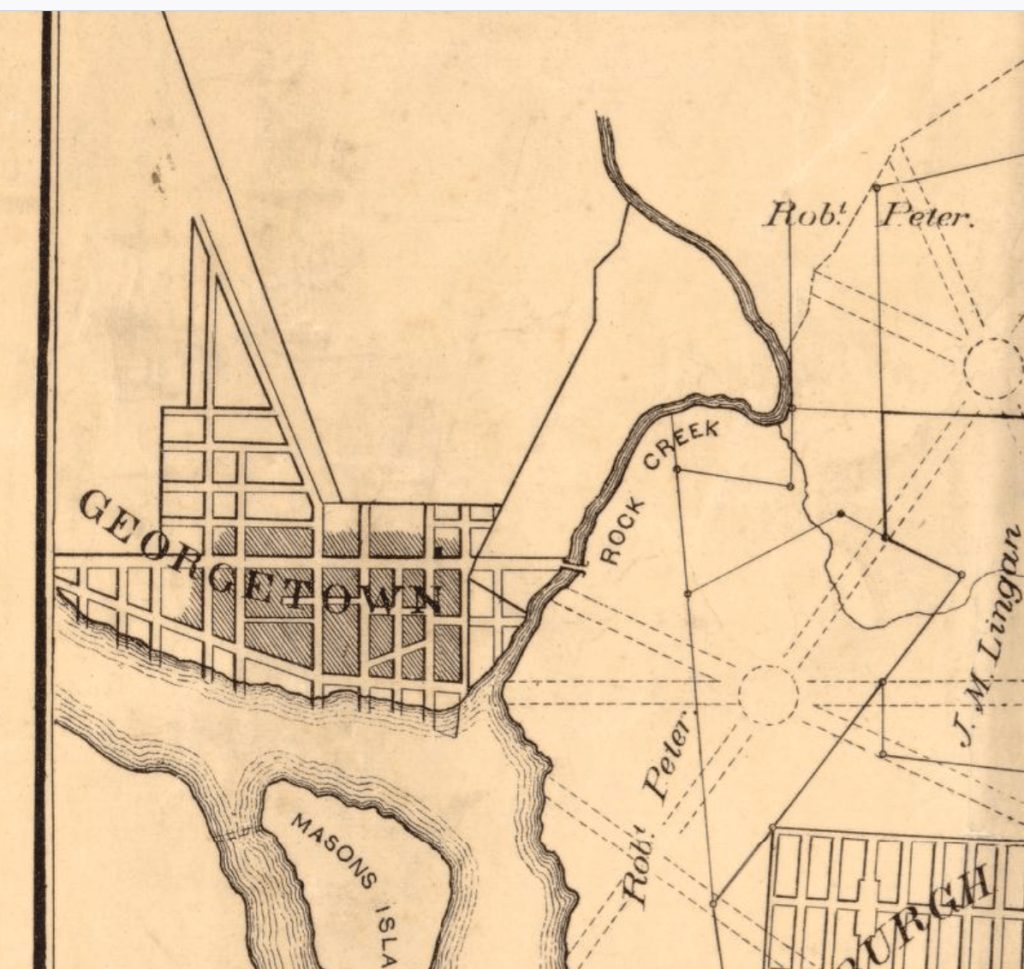

The advertisement’s location is given as “Rock Creek”, whereas the ad placed by Robert Peter a year earlier for Isaac and Sarah listed “Georgetown.” One of Peter’s many properties was the Rock Creek Quarter, a farm which appears to have been located along the eastern bank of Rock Creek. (Dr J.M. Toner’s map, “Washington in Embryo,” published in 1874, based on his own research on the landscape of the future District of Columbia before the Federal City was laid out around 1790, shows Rock Creek as rather wider than it is now, and indicates that Robert Peter owned an expanse of land east of the creek, from the Potomac River heading north.) Following his death, Rock Creek Quarters and its slaves and livestock were sold from Robert Peter’s estate on January 25, 1808 (the list of property is archived at Mount Vernon). Robert Peter’s general store is thought to have been located in the Wapping Quarter of Georgetown, on the west bank of Rock Creek. roughly where K street now crosses Rock Creek, underneath the present Whitehurst Freeway.

Tom’s Escape Route

Peter’s mention of a missing canoe implies that a canoe was regularly tied up on Peter’s Rock Creek property, perhaps near the general store or one of his creekside farms. it seems likely that a the time of his escape Tom would have paddled the canoe south to the creek’s mouth on the Potomac. Perhaps he headed downriver towards the Chesapeake Bay and then towards the open Atlantic. Or perhaps Tom tried to paddle up the Potomac, above the Fall line, traversing the treacherous rapids at Great Falls, in the hope of reaching Native lands in the interior.

Canoes as Vessels of Escape

It would of course be interesting to know more about the canoe that Tom liberated from Robert Peter in the process of hs escape. The Powhatan and other indigenous communities had used single log dugout canoes along the region’s waterways since time immemorial. The 18th century European modification of the dugout involved multiple logs and at times included masts and sails. These Chesapeake canoes were used by Chesapeake watermen well into the late 19th century. Chesapeake canoes are now regularly raced in the bay.

Canoes were used as vessels of self liberation in other instances. A decade after Tom’s, on December 19, 1771 the Maryland Gazette recounts an escaped enslaved man named Isaac in a small canoe being apprehended by a white Captain Scott; Isaac then escaped again.

On November 1, 1764, a Samuel Chew advertised that an Irishman named John Rice, an indentured servant, had escaped from him in Calvert County using a 25 foot stolen poplar canoe.

During the American Revolution, on October 2, 1777, John Cryer advertised that five enslaved people, three men and two young women, had escaped from him on Sharp’s Island (on the James River near Richmond, Virginia), in a large pine canoe, “well timbered.”

What Became of Tom?

As of this writing, I am unsure if Tom was recaptured and perhaps resold. It is possible that he is referenced in a different runaway ad, placed about eight months later on June 10, 1762 in the Maryland Gazette, by Caleb Dorsey, who ran the Elkridge Furnace, in Howard County, on the northwestern shore of the Chesapeake Bay:

“Six Pounds Reward

Ran away from the Elk-Ridge Furnace on the 26th of May last , Five Negro men, viz

One named Tom, he is a very cunning Rogue has often ran away and is very artful in sculking; the other four are New Negroes and can speak but very little English,

Whoever takes up the said Negroes, and bring them to the Elk-Ridge Furnace or secures them so that they may be had again, shall have six pounds reward, and reasonable charges paid by Caleb Dorsey

N.B. The negro named Tom, formerly belonged to Mr. Thomas Ringgold, and is very well acquainted with the Bay; therefore perhaps may attempt to escape by water.

This Tom’s previous owner, Thomas Ringgold IV (1715 – 1772) it should be noted, operated with his partner Thomas Galloway the largest slave trading operation in the Chesapeake Bay. It is not beyond the realm of possibility that Robert Peter upon recapturing Tom, sold him to Ringgold who in turn sold him to Dorsey. But since Tom is such a common name they could easily have been different people.

If nothing else, these various advertisements do suggest that for enslavers in the Tidewater, there were benefits and risks in owning enslaved people skilled in water navigation. Their nautical skills were valuable for all sorts of purposes, but also increased the chance they might hazard a waterborne escape.

As noted in my earlier post, Robert Peter’s ledger (Tudor Place Archives) does notate that on 23 May, 1795, Peter gave “Tom” 15 cents to pay “Ning” (Mary?) for a coat. Perhaps this was the same Tom, or a different man.